One orphaned calf is flourishing after being re-released into a preserve.

Rhinoceros populations are beginning to rebound in the species’ native home of Zimbabwe, a sign that efforts to preserve the species are working, according to animal conservationists.

The rhino population in Zimbabwe has surpassed more than 1,000 animals for the first time in more than 30 years, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature Species Survival Commission’s African Rhino Specialist Group. This includes 614 black and 415 white rhinos, listed as critically endangered and near threatened on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species, respectively.

Dedicated conservationists continue to persevere in protecting the country’s rhinos “with great success,” despite soaring costs for food and fuel, according to the International Rhino Foundation, which was founded 31 years ago amid a poaching crisis.

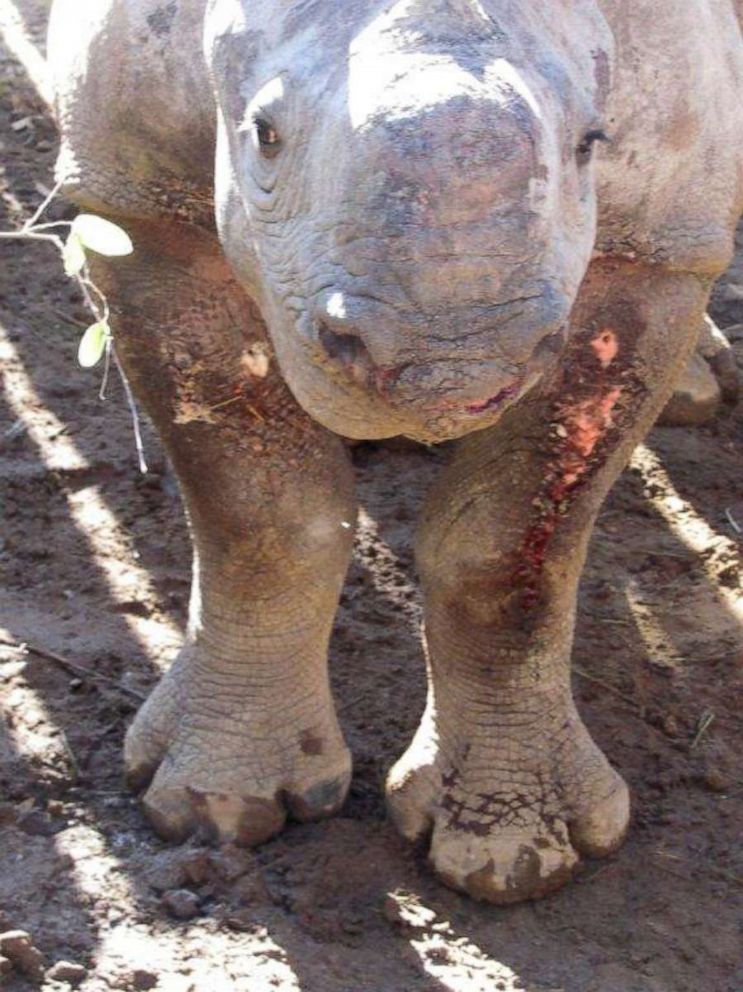

During a routine patrol in July 2020, conservationists from the Lowveld Rhino Trust found Pumpkin’s mother, who had been killed by poachers, Whitlatch said. Near her body, the conservationists noticed “little bloody footprints,” to which they tracked down Pumpkin, who was still alive but had been shot in the torso by the poachers and was severely injured, Whitlatch said. She was just about 16 months at the time.

Pumpkin’s will to live was apparent from the get-go, as were her “spunk” and “charisma,” Whitlatch said. She even took a bottle from her caregivers, a foreign concept to baby rhinos that gave them confidence that she would survive.

After some months of rehabilitation, Pumpkin was released back in October 2020 back into the protected land, home to most of the rhinos in Zimbabewe and where she continues to thrive today, Whitlatch said.

Pumpkin is monitored on a regular basis, and has even made the acquaintance of a young male black rhino of the same age named Rocky, giving conservationists hope that they will mate and reproduce, Whitlatch added.

However, it has still been a difficult year for rhinos, according to the International Rhino Foundation. After a temporary lull in poaching due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, criminal networks have quickly adapted to the new challenges, and poaching rates and trade volume have begun increasing again this year, according to the IRF.

“Large, organized crime groups, who see wildlife trafficking as low-risk, high-reward crime, became even more involved in rhino horn trade during the pandemic, monopolizing key networks and moving higher volumes of horn,” the conservation said in a statement.