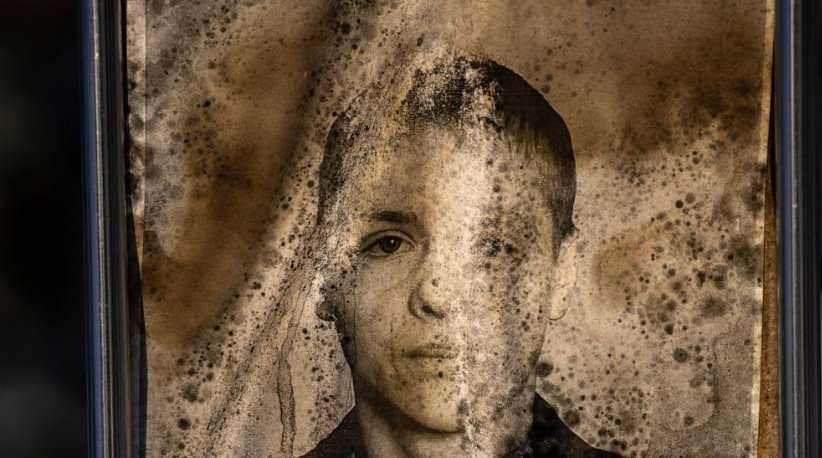

At a cemetery in Irpin, a suburb of Kyiv, photographs affixed to headstones are almost imperceptible

IRPIN, Ukraine — The ghostly gazes of Ukraine’s war dead are losing definition.

At a cemetery in Irpin, a suburb of Kyiv, photographs affixed to headstones are almost imperceptible. Exposed to rain, sun and frost since the war began nearly a year ago, the graveside portraits’ once-bright hues are fading away and yellow stains and mold are encroaching.

Among them is an elderly man who froze to death under Russian occupation, a young man believed to have been tortured and hanged, and an elderly woman who died alone and afraid.

The men and women buried between March and July in Irpin — and at cemeteries in Bucha, Kyiv, Lviv and beyond — are silent witnesses to the human cost of Russia’s invasion. Like their graveside photographs — a tradition in Ukraine — the stories of their lives are also at risk of becoming less clear: families have moved away, neighbors are losing their memories, and some relatives who remain are tired of recounting the sorrowful details.

After Russian forces’ brutal monthlong occupation of Irpin, Ukrainian soldiers retook the city at the end of March after fierce urban fighting. Residents there — and in Bucha and Hostomel, too — gave horrific accounts to prosecutors and journalists of violence and death suffered at the hands of Russian soldiers.

The photographs at the Irpin cemetery contain stories of their own.

In the worn-out portrait of Anatoly Olofunskyi, it is still possible to see the pattern of the military shirt the former soldier is wearing, though his facial features have become faint after a regular battering of snow and rain. His mother, Ludmilla, says she has changed the photograph twice since he died last spring.

Ludmilla keeps an unblemished copy of that photograph in her bedroom and starts each day by saying “Good morning, son.” At night, he appears in her dreams and tells her not to cry.

The day Ludmilla discovered her deceased 39-year-old son in the bathroom of his apartment down the street, he was hanging by his neck. A medical expert later told her that he had been bound and tortured.

Ludmilla says she has given up changing her son’s cemetery portrait, but she visits his grave regularly — and believes that he still communicates with her.

Once she saw two birds at his gravesite. She knew instantly what this meant. Anatoly had been unmarried when he died. “So,” she said, “you’ve finally found someone.”

At another gravestone nearby, a framed portrait of Dina Pivin hangs above the snow, her eyes, mouth and cheeks well-defined even as the rest of the image loses clarity.

She died alone in her flat at age 84, afraid to leave and without food. Her grandson, Serhii, had fled before the Russians arrived.

After the block her apartment is on was shelled, the building manager grew concerned because he hadn’t heard from her. He asked one of the cleaners to check on her. The man arrived and found the key still lodged in Pivin’s door, and the woman lying on the ground.

Long before the war, Halyna Mandrik had photos of herself and her husband, Volodymyr, printed and framed.

She wanted to make things easy for their children in the event of their deaths. The photos would be there, in plastic bags, ready to be nailed to the cross when their time came.

A photograph of Volodymyr, deeply faded and stained with mold, is now attached to his headstone. What is left of his facial features appears in a weathered shade of greenish-blue.

Because of a severe head injury Volodymyr suffered roughly 16 years ago, Halyna was unable to move him to their basement shelter when the Russian forces arrived. So she kept him in their bedroom.

Shelling had cut out the power, and the nights were freezing. Halyna was too scared to leave home to find firewood. She covered her husband with blankets and cooked for him, but in the last week of his life she said he stopped taking food. She didn’t know why.

One morning she awoke to find that Volodymyr, at 83, had died. “He froze,” she said, matter-of-factly.